Note: The following article was originally published in the Jerusalem Post.

The toppling of Bashar al-Assad’s government ends five decades of autocratic Baathist rule in Syria, opening a new chapter in the country’s history. As Syrians enter a post-Assad era, the pressing question remains: what is the future of Syria?

For Syria’s new caretaker government, the risks are significant. It must tackle mounting challenges to establish stability and prevent a return to civil war, or risk plunging the nation back into uncertainty.

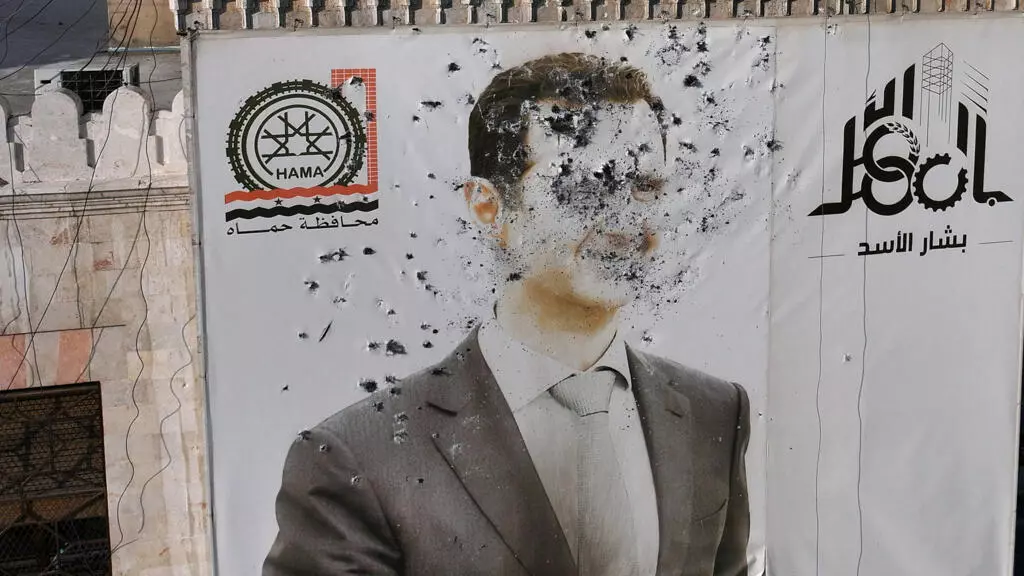

The Assad dynasty crumbled in mere weeks under a coordinated opposition offensive starting in late November 2024. The Islamist organization Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) launched “Deterrence of Aggression,” an operation that drove the Syrian Arab Army (SAA) out of Idlib province in the country’s northwest. Joined by fighters from the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) and remnants of the Free Syrian Army (FSA), the rebel coalition swiftly captured Aleppo before advancing south through Hama, Homs, and finally reaching Damascus on December 8th.

The rapid demise of the Assad regime exposed significant weaknesses in the government’s ability to exercise control and the fragility of its foreign support. Assad’s survival depended heavily on the backing from Tehran and Moscow, which provided logistical, political and military assistance during the country’s civil war. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) commanded the bulk of foreign Shiite fighters and other Syrian militias that would assist SAA units in combat—the IRGC also used Syria as a launchpad for supporting armed non-state actors against Israel like Hezbollah in neighboring Lebanon. Russia acted as Assad’s political guarantor by playing a crucial role in preventing the regime’s collapse in 2015, deploying military police, special forces, and utilizing airpower from its assets in Latakia and Tartus.

However, conflicts in Ukraine, Gaza, and Lebanon have strained these foreign state backers. Russia’s 2022 escalation in Ukraine required redeploying forces from Syria, weakening its regional influence and support for Assad. Israeli operations targeting IRGC-backed Hamas and Hezbollah leadership in Gaza and Lebanon from 2023 onwards have also disrupted Tehran’s capacity to project power. These external forces, along with Assad’s dependence on foreign patrons to maintain power, left Syria in an increasingly fragile state.

The ousting of Assad ends decades of Baathist rule, opening the door for Syria’s transition to stability. HTS leader Ahmed Hussein al-Sharaa (formerly known as Abu Muhammad al-Jolani) has established a caretaker government (Syrian Transitional Government) to oversee the move away from Baathism. A former al-Qaeda commander who was once associated with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the founder of Daesh, al-Sharaa now positions himself as a kingmaker for Syria’s future. While he has pledged to create a Syria that represents all its people, the ability of the government to fulfill this promise remains uncertain in the face of significant challenges.

Foreign involvement in Syria by multiple governments with sometimes opposing interests complicates efforts to unify the war-torn country.

Turkey occupies parts of Syria’s north while supporting the SNA, a group accused of harboring Salafi jihadists and serving as Turkish mercenaries, who are currently engaged in clashes with the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Governing a quarter of the country under the Democratic Autonomous Administration of Northeastern Syria (DAANES), the SDF is a multi-ethnic coalition led by Kurdish forces. Ankara aims to eliminate the SDF and establish a security zone along its border. Settling these tensions and integrating the SDF into a future national army will require making peace with Ankara that ensures the withdrawal of Turkish forces and protects minorities in the northeast.

The U.S. maintains a small contingent of special operations forces (SOF) in Syria’s northeast and southeast to prevent a resurgence of Daesh, a continuation of Operation Inherent Resolve aimed at ensuring the terrorist organization’s defeat. Thousands of Daesh fighters and their families are held in SDF-managed camps such as the under-resourced al-Hol refugee camp and in prisons located in places like Hasakah. Ensuring that these fighters are not released is crucial to preventing Daesh resurgence. Collaboration with the anti-ISIS coalition and the SDF to build robust security architecture is necessary to achieve this.

The presence of Israel in the southwest offers both a challenge and opportunity for the caretaker government. Israel has targeted Syria’s military infrastructure, including naval assets and chemical weapons facilities, amid concerns over the country’s instability. The prospect of Syria becoming a jihadist stronghold similar to Afghanistan poses an intolerable security threat to Israel.

Calls from HTS fighters to attack Israel from Damascus’s Umayyad Mosque are concerning and highlight the surge of extremism in the country. The caretaker government has an opportunity to address these issues through a formal peace settlement with Israel. This could potentially include negotiating the withdrawal of Israeli forces from the UNDOF buffer zone, security cooperation to curtail terrorism and Iranian aggression, and assistance for reconstruction.

Resolving domestic tensions will be integral to the success of al-Sharaa’s government.

Minorities across Syria are increasingly vocal about their concerns for the country’s future. Graphic images, videos, and testimonies from prisoners recently released from Assad’s infamous Sednaya prison underscore the brutality of the former regime and intensify calls for retribution. This has led to a rise in targeted attacks against Shiites and Alawites in areas such as Aleppo and Latakia, as well as unconfirmed reports of anti-Christian persecution. Adding to this atmosphere of violence is the lawlessness of armed gangs operating across the country, affiliated with both HTS and the SNA. Addressing this requires the immediate restoration of law and order, including open dialogue with the population’s various minorities such as Druze and Kurdish leaders.

A constitution rooted in the principles of Syria’s multiethnic, religiously diverse character is essential for the country’s future. The Baathist regime’s fatal mistake was centralizing power in Damascus while imposing an Arab nationalist identity that marginalized non-Arab populations. This system institutionalized ethnic discrimination, denying the existence and rights of minorities. A new Syrian constitution should aim to correct this by adopting a federal secular model that recognizes minority identities, protects their rights, and guarantees local autonomy. Such a framework would allow the country’s diverse communities to preserve their cultures, language and practises while ensuring unity within a united Syria.

A post-Assad Syria now is faced with a choice between two different futures: an Islamist autocracy run by disparate armed gangs that is a safe haven for extremists and a regional pariah—or a stable, renewed country founded on a constitution that represents inclusive governance. This requires integrating strong legal institutions that protect its population, upholds the rule of law, facilitates national reconciliation, and is an active partner in the international community.

The choice is up to Syrians to decide.

Written by Anthony Avice Du Buisson (20/01/2025)

![The responsibility to end the devil’s game in Afrin lies on us all – The Region [Article]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/5a77723f98666-700x465.jpg)