The Following article was originally published in The Region.

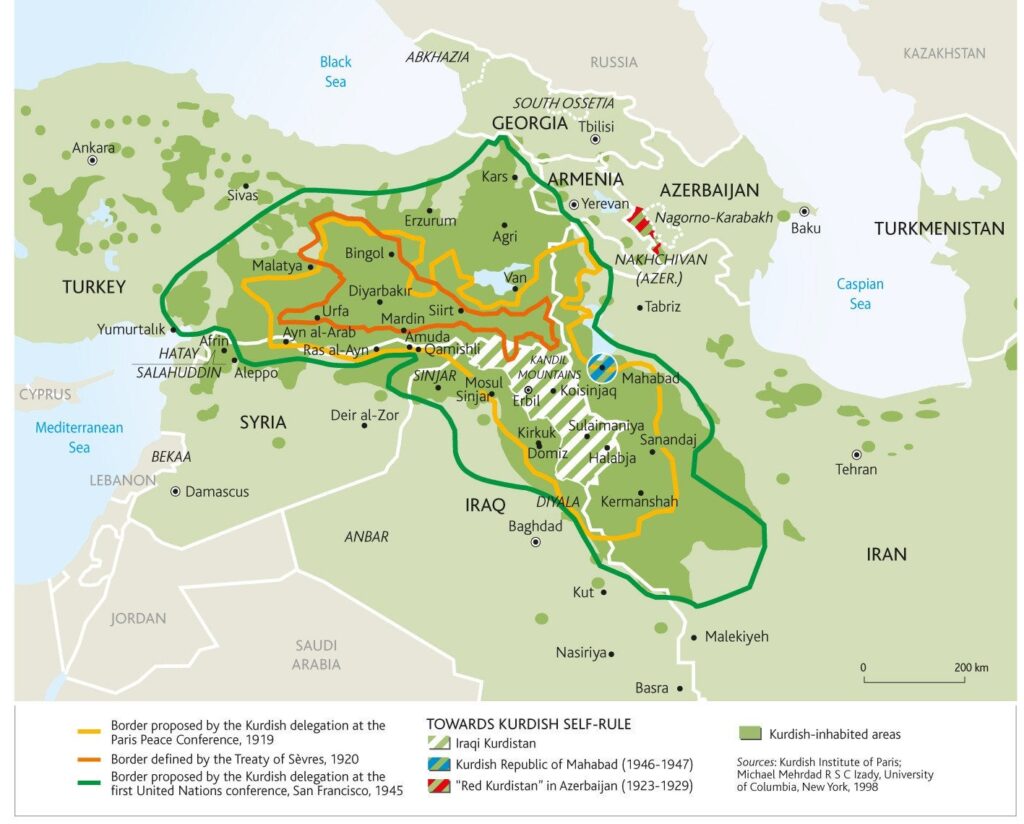

Syria’s Kurds are altering the political landscape of Northern Syria, reducing the power of Bashar al-Assad’s government and reorganising the power dynamics of the country – allowing for political and legal rights for Kurds, Assyrians, Syriacs, Turkmen and other minorities that were absent under Arab Socialist Baath rule. It is through the organisation of political and military resistance, the establishment of a place of authority while abstaining from taking sides in Syria’s civil war, as well as the engagement in the war against the Islamic State, that Kurds in Syria now are in process of achieving self-determination and autonomy. Kurds are one of the largest ethnicities in the Middle East with a population of over thirty million, occupying parts of Iraq, Syria, Iran and Turkey.

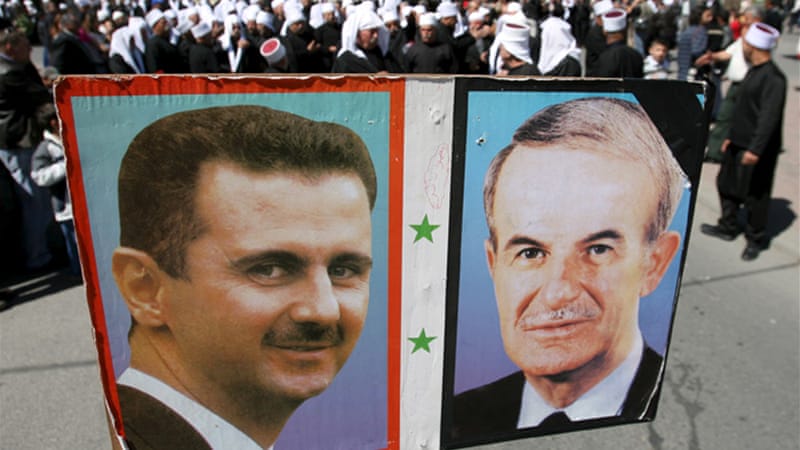

Descendants of Indo-European tribes that migrated westward from Zagros Mountains in Iran, Kurds have a distinct culture and identity that sets Kurds apart from other Middle Eastern ethnic minorities. In northern Syria, Kurds makeup 8-10% of the nation’s population (over thirteen million people) and have been the subject of Arab assimilation policies – Arabization. One such policy was conducted in Hassakah governate in 1962, when a consensus rendered over 110,000 Syrian Kurds without citizenship – giving these individuals status of ‘ajanibs’ (foreigners), while absentees were given status of ‘maktoumin’ or, ‘hidden’. Discrimination and persecution followed in subsequent decades, right into the early 21st century. When Syria fell into civil war after the wake of the Syrian revolution in 2011, Syrian Kurds revolted against Bashar Al-Assad’s government and started the ‘Rojava revolution’ – ‘Rojava’ is Kurdish for ‘Western Kurdistan’.

The Kurdish uprisings in Northern Syria have subverted the traditional authority of Bashar Al-Assad’s government, as political and military resistance has formed to resist Baath hegemony. ‘Power’, as defined by German sociologist Max Weber, is the potential of an actor to achieve personal objectives in a social relationship in the face of opposition. When a subordinate entity can limit or reduce the potential of an entity to achieve personal objectives, then that denotes ‘resistance’. For decades, the Arab Socialist Baath party government, under first the leadership of Hafez al-Assad and then Bashar al-Assad, enacted its power through coercion, fear, state repression, manipulation and bribery. Any other party, such as the Muslim Brotherhood that stood in the Baath party’s way would be heavily suppressed and have its members locked up in jail. Policies, such as those of assimilation and Arabization, aided in the consolidation of the government’s power and the pursuit of its aims – Arab nationalism.

When peaceful demonstrations in Damascus and Idlib were suppressed by Syrian government troops in 2010, armed resistance developed, as defectors of the ‘Syrian Arab Army’ (SAA) and local dissidents established the ‘Free Syrian Army’ (FSA) and its political wing ‘Syrian National Coalition’ (SNC). Uprisings occurred all over Syria, including Northern Syria in cities, such as Qamishli, Kobane and Afrin. These armed uprisings resulted in the start of a civil war between Syria’s government, FSA and Islamist entities of Al-Qaeda (JFS), and the Islamic state (ISIS) after 2013. However, what distinguishes the Northern Syrian Uprisings in 2012 from the other uprisings in the rest of Syria is the organisation and direction.

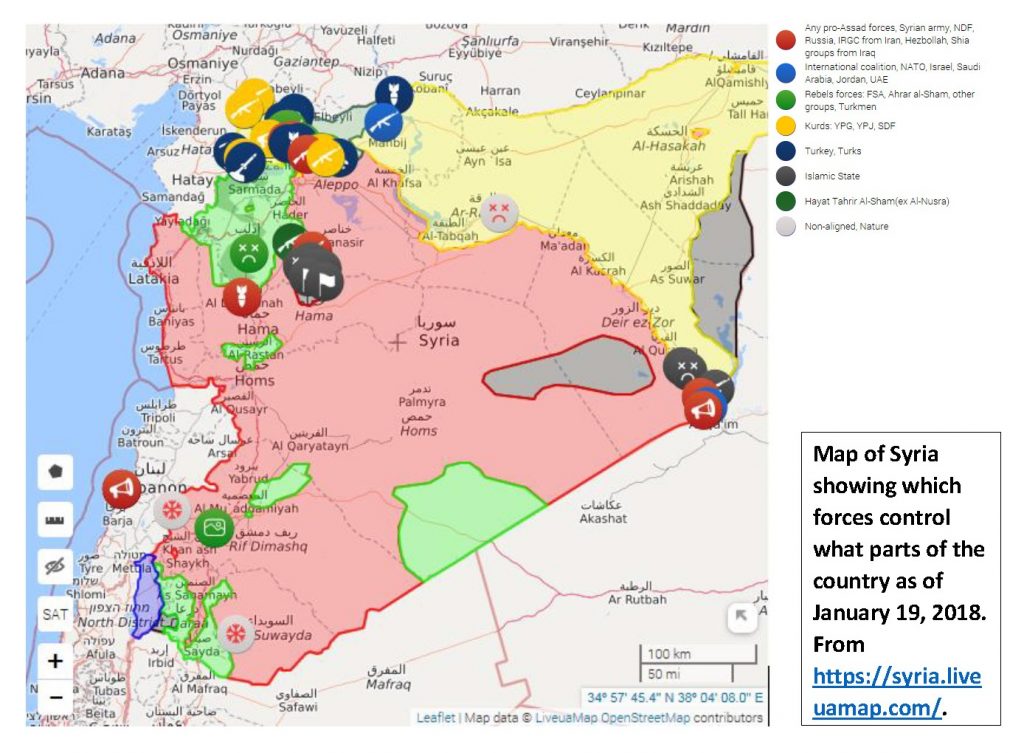

In 2012, the Syrian government was pushed out of Jazira (Cizire), Kobane and Afrin cantons by the organised local militia of the ‘People Protection Units’ (YPG) and its political wing, the ‘Democratic Union Party’ (PYD). Subverting Assad’s power in Northern Syria by exploiting the conflict dynamics of the civil war, with Assad’s forces focused on fighting FSA in other parts of Syria, PYD established a political alternative to Assad’s government with the formation of a de facto autonomous government – Rojava Autonomous Administration.

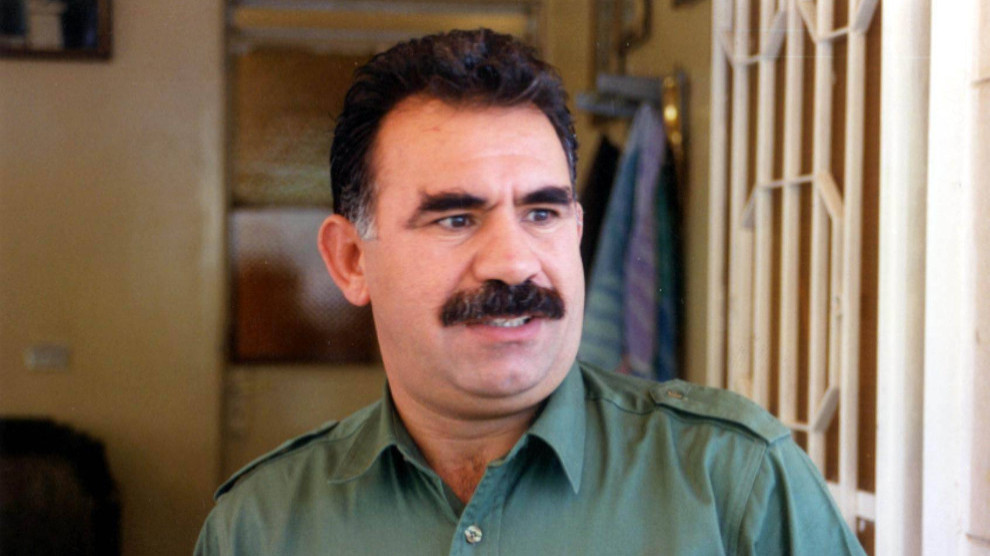

Organised under the ideology of Abdullah Ocalan, the founder of the ‘Kurdistan Worker’s Party’ (PKK), the PYD and other parties in the ‘Movement for a Democratic Society’ (TEVDEM) coalition (leadership of Rojava) adopted a ‘Democratic Confederalism’ ideology and implemented it in governance.

The ‘Rojava project’ spearheaded by TEVDEM undermines the ideology of Arab nationalism and the political hegemony of Assad’s Arab Socialist Baath Party, as the ideology of Democratic confederalism focuses on empowerment of minorities through local governance and aims at decentralising power – redistributing power among local municipalities. Instead of adopting a Kurdish nationalist project – similar to that of the ‘Kurdish Democratic Party’ (KDP) in Iraq – that aims at establishing a Kurdish region (Kurdistan), TEVDEM adopted a Democratic Confederalist project – similar to that of the PKK – that aims at establishing a grassroots, democratic and parliamentary system:

…[TEVDEM] sought a bottom-up system of self-administration whereby the direction of the flow of power is from the local municipally organized councils toward a larger democratic confederation of libertarian municipalities with local councils directly controlling policy-making. Such organization of politics is to provide it with concrete social content and reduces the likelihood of potential relations of domination, thereby contributing to advancing the cause of freedom as non-domination.

– Democratic Confederalism in TEVDEM system.

Through the implementation of the ideology of Democratic Confederalism in Rojava’s Autonomous Administration in Northern Syria, the influence of the ideology of Arab nationalism that had disenfranchised non-Arabs was significantly reduced. Kurds and other minorities in Northern Syria, such as Syriacs and Assyrians, could now establish local assemblies – form militias, police and self-administrate. This system decentralises power and prevents power from establishing in one party, thus weakening Assad’s central government in Damascus, and preventing it from having total domination in Northern Syria.

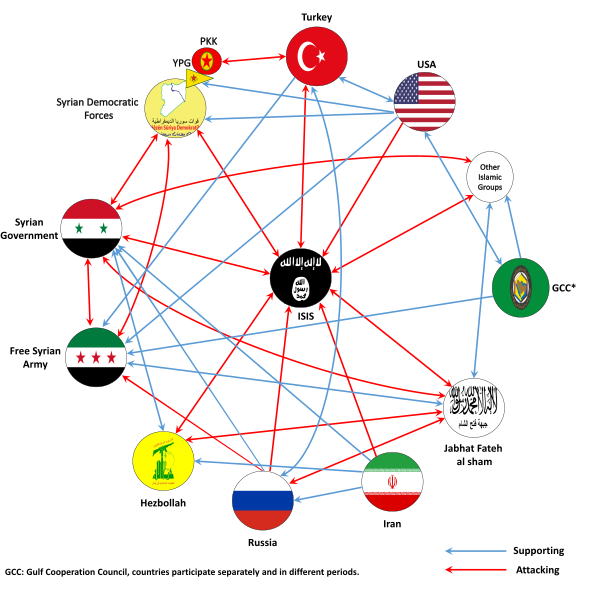

The opposition to taking sides in the Syrian Civil war and the fight against the ‘Islamic State of Iraq and Syria’ (ISIS), significantly increased TEVDEM’s influence in Syria’s political landscape and increased western support for the Rojava project – altering Syria’s power dynamics, and allowing TEVDEM more territorial control and political power. A strategy was adopted early on by the Rojava Autonomous Administration to not officially declare allegiance to any side in Syria’s civil war, instead opting to provide a ‘third path’ to the competing factions (Government forces versus rebels). This strategy aimed at allowing TEVDEM to focus on self-governance and self-defence, while keeping the war from reaching the de facto borders, therefore allowing TEVDEM to not lose local support and allow negotiation power with both sides, if need be.

However, despite YPG clashes between both the FSA, JFS and SAA, the introduction of ISIS in 2014 would significantly alter TEVDEM’s trajectory. The Siege of Kobane in 2014 by ISIS, brought global media attention to Rojava and increased the reputation of TEVDEM within the International Community. A victory by Kurdish forces against ISIS in 2015 helped boost the reputation of TEVDEM to the world, as the victory appealed to all sides of western political landscape. Conservatives had a force to support that was ‘western’ and radical Leftists could sympathise with the Rojava revolution, and the broader Kurdish struggle at large. The United States-led Coalition to battle ISIS formed a military alliance with Rojava at Kobane, which started with the US supporting and supplying arms to YPG, as well as other militias.

Capitalising off this new-found support, TEVDEM mobilised forces to resist an ISIS occupation in order to increase influence in Syria’s political landscape, liberate civilians and expand the borders of the de-facto Autonomous region through the acquisition of territory. The Islamisation of the opposition to Assad had also contributed in bolstering a number of defectors to Rojava, as former secular FSA factions started aligning with YPG – this led to the formation of ‘Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF) in late 2015, a multi-ethnic coalition of anti-ISIS fighters.

The success of Rojava against ISIS and the territorial expansion of the de facto autonomous region’s borders altered Syria’s power dynamics, as TEVDEM posed an increasing threat to Assad’s government and legitimacy. The acquisition of oil fields has expanded Rojava’s economic and political power, as TEVDEM has the leverage to negotiate its future and achieve Rojava’s goals of self-determination, as well as autonomy for Syrian Kurds and other minorities. Though the war is not over, Rojava’s Autonomous Administration is in a greater position than ever before in its short history to negotiate and achieve its personal objectives, despite resistance by Assad’s government and external threats, such as ISIS, the Turkish State and JFS (now Hay’at tahrir al-sham – HTS).

However, as with everything in the Syrian conflict, the precarious nature of these relations and situations can change at any moment. In the recent months for example, with the liberation of Raqqa by the SDF, Turkish-US relations have begun to heat up.

A new offensive into Idlib by the Syrian government and its allies in 2018 has given way to a Turkish offensive (Operation Olive Branch) in the Afrin canton of Rojava. The power dynamics are shifting and TEVDEM officials face a difficult uphill battle in 2018. Despite these difficulties, the determination of Rojava forces are stronger than ever before and international support for Rojava continues to grow with each passing month.

Turkey’s government views the PYD as an extension of the PKK in Syria, which it has been fighting internally since 1984. To the Turkish state, the presence of Rojava is a national security concern, as the entire area is considered a terrorist statelet – as well as a potential rally point for Kurdish dissidents within its borders. Turkish forces (TSK) backed FSA units (TFSA) in mid-2016 initiated an offensive (Operation Euphrates Shield) to take the northern Syrian city of Jarabalus and cut off the YPG’s expansion in Northern Syria. Wedging between Kobane canton and Afrin Canton, TFSA and TSK aimed to separate these cantons from one another. Further emphasising the top priority of Rojava in Turkey’s broader objectives in Syria.

Through the organisation of political and military resistance to Assad’s government, the establishment of an alternative government and abstaining from taking sides in Syria’s civil war, as well as the engagement in the war against the Islamic State, Kurds in Syria now are in process of achieving self-determination and autonomy. The implementation of the ideology of Democratic confederalism in Rojava Autonomous Administration governance has challenged the hegemony of Bashar al-Assad and the ideology of Arab nationalism, empowering the disenfranchised in Syrian society. The war against ISIS has allowed TEVDEM to acquire territory and has led to the alteration of power dynamics within Syria, allowing for Rojava to have greater potential in pursuing its own personal objectives.

Written by Anthony Avice Du Buisson (20/11/2017).