Note: The following article was originally published as an essay for John Hopkins University’s SAIS Europe Journal of Global Affairs, specifically in volume 25: Orae. It was uploaded in 2022.

Introduction

The influx of refugees to Europe in the wake of rising conflict in the Middle East and North Africa has reshaped European thinking around refugee policy in a substantial way. Research conducted by the European Social Survey shows an increase in negative attitudes toward refugees among Europeans.1 These attitudes spurred on by fears over security and identity have contributed to the bolstering of the European Union’s deterrence regime. This deterrence regime is set up through the auspices of the European Union (EU) with the aim of limiting the flow of refugees to mainland Europe.

Through agencies such as Europe’s Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) that monitor illegal migration along the periphery of the Union, the borders of Europe are monitored extensively. Along with these agencies the EU utilizes bilateral cooperation agreements between Turkey and Afghanistan to control migratory routes through third countries in exchange for economic guarantees. It is hoped by the EU that this approach will address Europe’s domestic challenges, notably as relating to security, extremism, and rising anti-EU sentiment.

However, the recent security dilemmas arising from Turkey and the Polish-Belarus border are exposing vulnerabilities in the system. These vulnerabilities are rooted in the securitarian approach the EU has taken in handling the crisis. Not only is this approach short sighted but it also undermines the humanitarian philosophy of the 1951 Refugee Convention by shifting responsibility away from states to protect refugees, encouraging the limiting of free movement and contributing to an increase in harm towards refugees.2 An approach that if pursued long enough will turn Europe from a bastion for all peoples to a fortress for the few.

The Origins of the 2015 Refugee Crisis

“We the people have legitimate demands, and we would like to tell the government what to do. Our freedom is not up for negotiation.“3

– Mohamed ElBaradei

The Arab Spring that started in the early 2010s encouraged a wave of democratic optimism across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Millions of people took part in large-scale demonstrations in countries such as Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, and Syria demanding democracy, equality, and justice. These civil protest movements undermined the authority of longstanding autocratic dictatorships that ruled with impunity. Revolutions soon arose across the region demanding an end to years of tyranny. Tunisia and Egypt were the first to overthrow the rule of Ben Ali and Hosni Mubarak regimes respectively. Revolutions in Libya, Yemen and Syria soon followed but took a drastically different direction when government crackdowns in those countries sparked armed resistance, which led to civil conflict.4

The collapse of the Syrian and Libyan states pushed millions of people to flee abroad. Tearing families apart, upending livelihoods and fracturing communities, places that many once called home ceased to be safe. Over three million people displaced from their homes in Syria fled to neighboring Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. As for the Libyan conflict, over two million displaced fled to neighboring Tunisia, Egypt, Sudan, and Algeria.5 These conflicts sparked humanitarian crises that heavily changed the dynamics of the region. These crises being exacerbated further by the rise and expansion of the Islamic state of Iraq and Syria.6

With no sign of conflict ending in Syria and a renewal of unrest arising in Libya and Iraq, neighboring states no longer could deal with rising refugee numbers. Jordan and Egypt’s refugee camps were overwhelmed with displaced people.7 This forced these states to adopt hard border approaches–rapidly closing borders and significantly restricting asylum seekers from entering. It was these rising restrictions that pushed people to flee farther afield to Europe.8 The conscience of Europe was directly besieged by the mass migration of people seeking refuge within the Union. Humanitarian crises previously thought of as far away from Europe’s gaze now could not be ignored. It was at this moment in mid-2015 that the current “refugee crisis” emerged prominent in political and migratory discourse.

Over a million displaced people fled into mainland Europe from the MENA region following the start of the crisis. Many refugees utilized migrant routes from North Africa and Turkey to cross the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas into Italy and Greece, where many more ventured through land routes in the Balkans to reach countries like Hungary and Germany. This mass movement of people is the largest in Europe’s history since the second world war.9 With 1.3 million first time applicants applying for asylum in Europe, the Common European Asylum system (CEAS) and Europe’s Border and Coast Guard Agency (Frontex) responsible for the processing of migrants and the security of the seas around Europe quickly were overburdened.10

However, not everyone reached the shores of Europe. Paying smugglers thousands of dollars to be cramped in overcrowded boats, many families endured the risks of drowning at sea to venture to Europe.11 Thousands died because of these desperate voyages. A notable example is the case of Alan Kurdi: a Kurd from Kobani who–along with his family–paid smugglers over five grand in US dollars to cross the sea into Greece.12 Only three-years old at the time, Alan (Alyan) Kurdi took a small five-meter boat with twelve other people including his mother and brother and attempted to cross the Aegean Sea. Equipped with faulty life jackets provided by smugglers, the vessel capsized in the early hours of the morning of 2nd of September 2015. His body washed ashore on the Turkish beach of Bodrum, where it was found by the Turkish authorities and later photographed by the press.13 Alan Kurdi’s death represents one case in over three thousand of displaced people that have perished during the perilous journey across the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas.14

In response to the crisis the European Union adopted a series of emergency policies that aimed at enhancing Europe’s security and reducing the flow of migrants to Europe. Among these policies included expansions to Frontex, Europol and the European Asylum Office (EASO) in charge of CEAS. These agencies represent some of the mechanisms that the Union utilizes for its security, as many are on the frontline in dealing with challenges such as crime, smuggling and illegal migration. All these enhancements to Europe’s security apparatus are a product of the European Commission’s proposed Agenda on Migration and Security in 2015.15

The European Union pushed forward with these policies to address not only the growing security issues that came with the refugee crisis but also growing anxieties. Terrorist attacks in Paris in January and November, along with rising violence in cities like Cologne, Germany fueled anti-refugee sentiment. Reactionary populist movements such as Pegida in Germany, the National Front in France, and conservative leaders such as Victor Orban in Hungary capitalized on fear to gain momentum for their political ambitions. Levelling blame for the crisis on the European Union, many of these movements and leaders have called for their respective countries to abandon the Union and adopt more hard border policies to stop migrants–calls that have gained traction and seen a resurgence in Euroscepticism.16

However, the Union’s security apparatus still struggled under the weight of incoming refugees. Mounting pressure pushed European policy makers to seek out bilateral cooperation agreements with third countries, such as Turkey to ease the flow of migrants. Controlling the main migration routes to Europe was important for the EU, so in 2016 it signed the EU-Turkey statement and joint action plan. On paper this agreement meant that Turkey would help regulate the flow of refugees with more stringent border policies in exchange for over six billion Euros from the EU.17 Another agreement with Afghanistan also followed with similar principles to that of the EU-Turkey agreement, except with an added emphasis on returning asylum seekers rejected back to Afghanistan–this applies to the “Joint Declaration” signed in 2020 too. In the case of both agreements, the priority of the Union is to ensure that the flow of migration is kept restricted, while also providing a place outside the Union for Asylum seekers to be returned with little to no reporting mechanisms used.18

Fortress Europe

“Wir haben so vieles geschafft – wir schaffen das.”19

– Angela Merkel

There is a deep sense of irony in the way Europe has approached the refugee crisis. Thousands of asylum seekers remain at an arm’s length from sanctuary in the European Union. This is despite the proclamations of European leaders like former German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who called upon Europe to meet its obligations to take in refugees in the early months of the crisis. What the Union has done in the last couple of years is shift away from its humanitarian obligations as enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention and moved towards a securitarian approach to the crisis. Critics label this new approach as “Fortress Europe”,20 an idea that rests on the notion that the Union is a homogenous entity with borders that must be “safe guarded” from the incoming flux of migrants. The idea is centered on viewing these incoming migrants as potential threats that undermine the Union’s security, sovereignty, and identity. Where the irony arises is that in the pursuit of curtailing reactionary sentiment, the Union has instead fueled it with its deterrence regime contributing to rising anti-immigrant and anti-EU sentiment.21

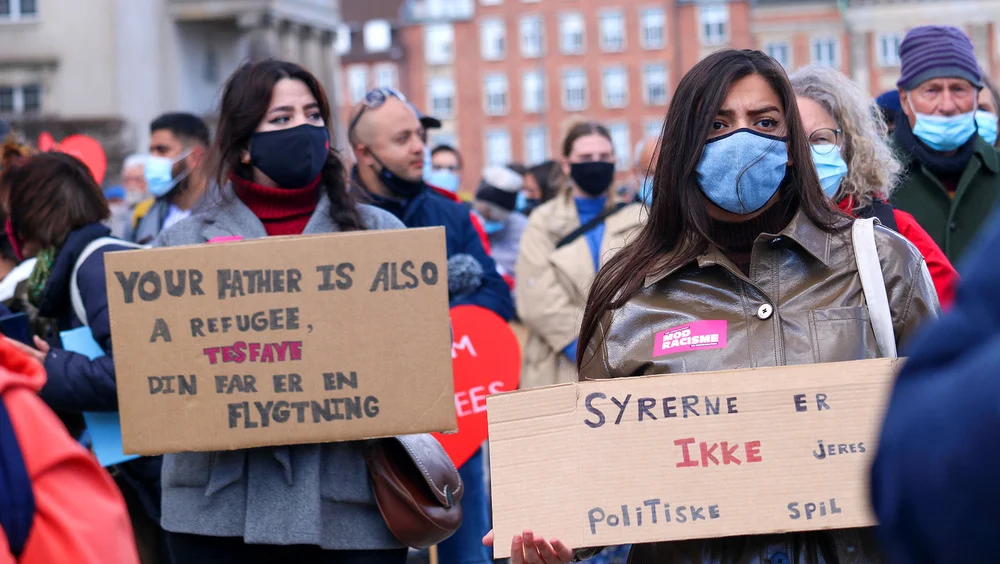

Denmark is a prime example where the tide of anti-immigration sentiment has taken hold. Syrian refugees previously settled in the country since the inception of Bashar al-Assad’s war on his people are now being returned to Syria. The reason? The Danish government considers the war to largely be over and safe for displaced people to return. Stripping hundreds of their residency permits, the government’s police are putting many after years of staying in the country back on planes headed for Damascus, Syria.22 This assessment by the Danish government largely ignores the risks associated for many who will be sent back to Assad’s Syria. Assad’s internal security forces continue to keep tabs on those that have fled, with severe imprisonment and disappearances remaining as consequences awaiting those returning. Yet, this is to be expected when there is a lack of a coherent proactive policy in dealing with the refugee crisis. When the focus is aimed at maintaining the security, sovereignty and identity of Europe, obligations to those people who have come from outside get ignored.

A clear contradiction exists with this “Fortress Europe” mindset and the aims of the Union’s refugee regime, as anchored by its humanitarian obligations under the Convention. The human rights of refugees are increasingly put aside in the interests of national security, while free movement is heavily curtailed by restrictions due to stringent border policy and lengthy asylum processing. Refugees who flee to get away from persecution in their home countries are blocked, whether it by land or sea, from seeking sanctuary in Europe. Those who can achieve asylum within the EU face a wave of discrimination, which is only further fueled both by reactionary movements within the host countries that associate criminality with refugees. The recent border crisis along the Polish-Belarussian border exposes vulnerabilities in the deterrence regime of the Union.

When Alexander Lukashenko, dictator of Belarus, threatened last year to “flood” Europe with migrants from mostly Iraqi Kurdistan, the EU’s Polish authorities pursued a hard border approach to prevent these migrants from entering the Union. Thousands of migrants, with little choice provided to them by the Belarussian authorities, were forcefully marched to the Polish border. In response, Polish authorities sent security forces accompanied by armored vehicles to push back the migrants so that a defacto border wall could be reinforced at many checkpoints along the Polish border.23

The reactive nature of Polish authorities to this border crisis instigated by Lukashenko regime is emblematic of the EU’s handling of the refugee crisis. Instead of adopting a proactive approach to deal with the causes for refugee migration and meeting obligations to protect those most vulnerable, Polish authorities, along with the rest of the EU, reacted to the crisis in a defensive manner. Ignoring the agency of those at the heart of the crisis, the EU reinforced border restrictions and sent security forces to deal with the “security” threat. This concerted effort to keep migrants out left over a dozen dead due to freezing temperatures. Humanitarian aid did not arrive, only exacerbating the situation, and application claims to the EU were outright denied without any proper review. The Union views this response as a success for its security apparatus in the defence of the Union. This is despite thousands of refugees essentially being forced back home.24

Poor handling of the border crisis is not the only incident where the vulnerabilities of “Fortress Europe” are on display. Another example is intertwined with the EU-Turkey deal that was signed in 2016. Since control of the main migratory route into the Union is held by Turkey, the country effectively acts as a valve controlling the amount of pressure the EU deals with. This vulnerability has been exploited by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan who, like Lukashenko, repeatedly has threatened to “flood” the EU with migrants whenever economic demands are not met or criticism has been made against Turkey’s military actions in neighboring states. Each time threats like this have been made, the EU has been quick to muzzle past criticisms and essentially appease Turkey in the process of acquiescing to its demands.25

Rethinking Refugee Policy

“Humanitarian response, sustainable development, and sustaining peace are three sides of the same triangle.”26

– Antonio Guterres

As mentioned before the European Union does not currently have a proactive approach to dealing with the refugee crisis. It instead has a series of policies that are reactive in nature that only seek to respond to the crisis from a security standpoint. This approach needs to be rethought and a new fresh mindset to replace the “Fortress Europe” one needs to be adopted.

The proactive approach that should be adopted needs to come from a place of humanitarian concern rather than security. This requires rethinking refugee policy entirely to actively address the root causes for migrations from failed states. Refugees do not flee to Europe purely for economic opportunities. Most are forced out of their homes due to insecurity caused by the failure of state structures in their countries. Addressing those failed state structures may provide a starting point for policy makers in dealing with the crisis for good. Stabilizing places where war is ongoing so that these areas are safe once again eliminates some of the root causes for refugee migration. This requires an active approach that aims at upholding international obligations to protect the vulnerable and facilitate peace.

A proactive approach involves a combination of diplomatic, economic, and military means to resolve the tensions in the middle east and north Africa region. What this fundamentally means is addressing the root causes for state disintegration.

For example: the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad remains in Syria. Even though a large amount of the fighting in the country has ceased, the root cause for the uprisings–the autocratic rule of Assad–remains and is likely to create potential issues in the future. A concerted multilateral initiative spearheaded by the Union that utilizes economic sanctions, military prowess and promotes political alternative can help deal with the conflict. For instance, the EU should adopt economic sanctions in line with the US Caesar Act sanctions on the Assad’s regime to curtail its autocratic abuses. It should also back The Autonomous Administration of Northeast Syria’s “Rojava project”–a project founded on democratic, decentralized, multiethnic, and feministic principles–provides a legitimate model of governance that Europe can back as an alternative to Assad’s rule.

The point is that eliminating the root causes for the crisis through the stabilization of regions where refugees come from helps both the EU and the displaced fleeing their homes. It helps Europe meet its humanitarian obligations per the 1951 Convention, while also significantly reducing the number of refugees fleeing into the Union as well as its dependence on third countries to regulate migration. It saves the Union billions of Euros in the long run as well, as current costs for border security will likely continue to go up with subsequent refugee waves. Fundamentally providing those at the center of the crisis–migrants–an ability to return and prosper once more.

Conclusion

The refugee crisis that followed from the onset of conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa region in early 2010s changed Europe substantially. Millions fleeing their home countries made way to Europe to seek out safety and security. An overwhelmed European Union shied away from its humanitarian obligations, instead choosing to pursue a security focused and ultimately, “Fortress Europe” mindset in handling the crisis. Spending billions on Frontex, Europol, CEAS and EASO, the Union has enhanced its deterrence regime to bolster this securitarian approach. Bilateral cooperation agreements with Turkey and Afghanistan help regulate the flow of migrants but expose vulnerabilities in Europe’s dependence on third countries. With recent crises such as the one on the Belarus-Polish border and frequent Turkish threats to flood Europe with migrants, the EU is increasingly stuck with reactionary policies that fail to solve the crisis.

As argued in this paper, for the European Union to potentially solve the crisis it must adopt a proactive approach that reorientates the mindset away from “Fortress Europe” to a humanitarian one. Taking proactive measures with economic, military, and diplomatic intervention in failed states to stabilize those states is imperative. Addressing the root causes of the refugee crisis is the only way for Europe to meet its humanitarian obligations, reduce migrant flow and solve the crisis.

Those of us who live in the Anglosphere or Europe itself can either solve this crisis together or continue to let it fester for future generations. I believe that we have a humanitarian obligation to those most vulnerable who are suffering greatly. That obligation rests on a common humanity built on compassion, solidarity, and unity. We must take the side of the victim and aid them in their struggle if we truly believe in this project. We cannot just speak; we must act.

Written by Anthony Avice Du Buisson (Summer 2022)

Footnotes

- Christian S. Czymara, “Attitudes Toward Refugees in Contemporary Europe: A Longitudinal Perspective on CrossNational Differences,” Social Forces 99, no. 3 (2021): 1316.

- United Nations General Assembly, United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, https://www.unhcr.org/en-au/3b66c2aa10.

- Jack Shenker, “Mohamed ElBaradei Urges World Leaders to Abandon Hosni Mubarak,” The Guardian, February 2, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/feb/02/elbaradei-abandon-mubarak.

- Mehari Fisseha, “The Roles of Civil Society and International Humanitarian Organizations in Managing Refugees Crisis in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region,” Journal of Mediterranean Knowledge 3, no. 1 (2018): 63-7.

- Ibid.

- Aziz Douai, Mehmet Fatih Bastug, and Davut Akca, “Framing Syrian Refugees: US Local News and the Politics of Immigration,” The International Communication Gazette (March 2021): 94.

- Laura Zanfrini, “Europe and the Refugee Crisis: A Challenge to Our Civilization,” United Nations Academic Impact, 2021, https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/europe-and-refugee-crisis-challenge-our-civilization.

- Ibid.

- Kyilah Terry, “The EU-Turkey Deal, Five Years On: A Frayed and Controversial but Enduring Blueprint,” Migration Policy Institute, April 8, 2021, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/eu-turkey-deal-five-years-on.

- Ninna Nyberg Sørensen et al., “Europe and the Refugee Situation: Human Security Implications,” Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) no. 3 (2017): 11.

- Leila Simona Talani, “The 2014/2015 Refugee Crisis in the EU and the Mediterranean Route,” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 22, no. 3 (2020): 452-54.

- Teresa Wright, “Alan Kurdi Photo Spurred Canadian Government Scramble to Respond, Documents Reveal,” The Globe and Mail, April 29, 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/politics/article-alan-kurdi-photo-spurred-canadiangovernment-scramble-to-respond/.

- Joe Parkinson and David George-Cosh, “Image of Drowned Syrian Boy Echoes Around World,” Wall Street Journal, September 3, 2015, https://www.wsj.com/articles/image-of-syrian-boy-washed-up-on-beach-hits-hard-1441282847.

- The Visual and Data Journalism Team, “Hundreds of Migrants Still Dying in Med Five Years Since 2015,” BBC News, September 1, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53764449.

- Susan Ferreira, “From Narratives to Perceptions in the Securitisation of the Migratory Crisis in Europe,” EInternational Relations, September 3, 2018, https://www.e-ir.info/2018/09/03/from-narratives-to-perceptions-in-thesecuritisation-of-the-migratory-crisis-in-europe/.

- Thomas Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nikolas F. Tan, “The End of the Deterrence Paradigm? Future Directions for Global Refugee Policy,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 1 (March 2017): 33-35; Talani, “The 2014/2015 Refugee Crisis,” 15-17.

- Sørensen et al., “Europe and the Refugee Situation,” 11.

- Mojib Rahman Atal, “The Asymmetrical EU-Afghanistan Cooperation on Migration,” The Diplomat, May 12, 2021, https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/asymmetrical-eu-afghanistan-cooperation-onmigration/#!#:~:text=On%20April%2026,%20the%20European,in%20the%20EU%20member%20states.

- Janosch Delcker, “The Phrase that Haunts Angela Merkel,” Politico, August 19, 2016,

https://www.politico.eu/article/the-phrase-that-haunts-angela-merkel/. - Stefan Lehne, “The Tempting Trap of Fortress Europe,” Carnegie Europe, April 21, 2016,

https://carnegieeurope.eu/2016/04/21/tempting-trap-of-fortress-europe-pub-63400. - UN General Assembly, Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees.

- Charlotte Alfred and Benjamin Holst, “How Denmark’s Hard Line on Syrian Refugees is an Aid Group’s Ethical Dilemma,” The New Humanitarian, January 11, 2022, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2022/1/11/how-Denmark-hard-line-Syrian-refugees-aid-group-ethicaldilemma#:~:text=Denmark%20is%20the%20first%20European,right%20to%20work%20since%202019.

- Lydia Gall and Tanya Lokshina, “Die Here or Go to Poland: Belarus’ and Poland’s Shared Responsibility for Border Abuses,” Human Rights Watch, November 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/11/24/die-here-or-gopoland/belarus-and-polands-shared-responsibility-border-abuses.

- Ibid.

- Sørensen et al., “Europe and the Refugee Situation,” 11.

- Antonio Guterres, “Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ remarks to the General Assembly on Taking the Oath of Office,” United Nations Secretary-General, December 12, 2016, https://www.un.org/youthenvoy/2017/01/secretarygeneral-antonio-guterres-remarks-to-the-general-assembly-on-taking-the-oath-of-office/.

![The American-Australian alliance: ANZUS role in Australian History [JCU Essay]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Australia-US-Talisman-Saber-Exercises-Soldier-June-28-2017-700x465.webp)

![Dandelion a Drift – [Personal Writing]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/10687325_722474704495662_2620316147957936033_o-700x465.jpg)

![A Broken Hall of Mirrors – [Short Story]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/11231699_879026565507141_1680011889352418125_o-700x465.jpg)