Note: The following article was originally uploaded as an assignment for James Cook University – PL3250: Australia and World Politics. It was uploaded in 2019.

The Australian government’s role in the stabilisation of the Solomon Islands in the early 2000s was crucial to the restoration of law and order in the state. A diplomatic peace initiative through the Pacific Islands Forum allowed for the John Howard government to broker negotiations amongst warring militias. Howard’s government used the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI) to provide military and political assistance, contributing to the disarmament of militias, a peaceful resolution of ethnic tensions and the internal reestablishment of law and order in the Solomon Islands. This ultimately benefiting Australia’s national security in the South Pacific. Through the analysis of the ethnic tensions between Malaitan and Guadalcanalese peoples in the Solomon Islands and Australia’s bilateral relations with the Solomon Islands’ government during the Tension period, it will be shown the security issue the situation in Solomon Islands increasingly posed to Australia’s regional security. An argument then will be made that Australia’s intervention into East Timor in 1999 greatly influenced its approach to its national security in the South Pacific, notably in helping to influence it in taking a proactive approach in stabilising an emerging arc of instability in the region. This proactive approach coming in the form of diplomatic and military intervention, such as in the case of the Solomon Islands through the peace initiative set out first diplomatically with the Townsville agreement, and then militarily through RAMSI in order to restore order in the nation.

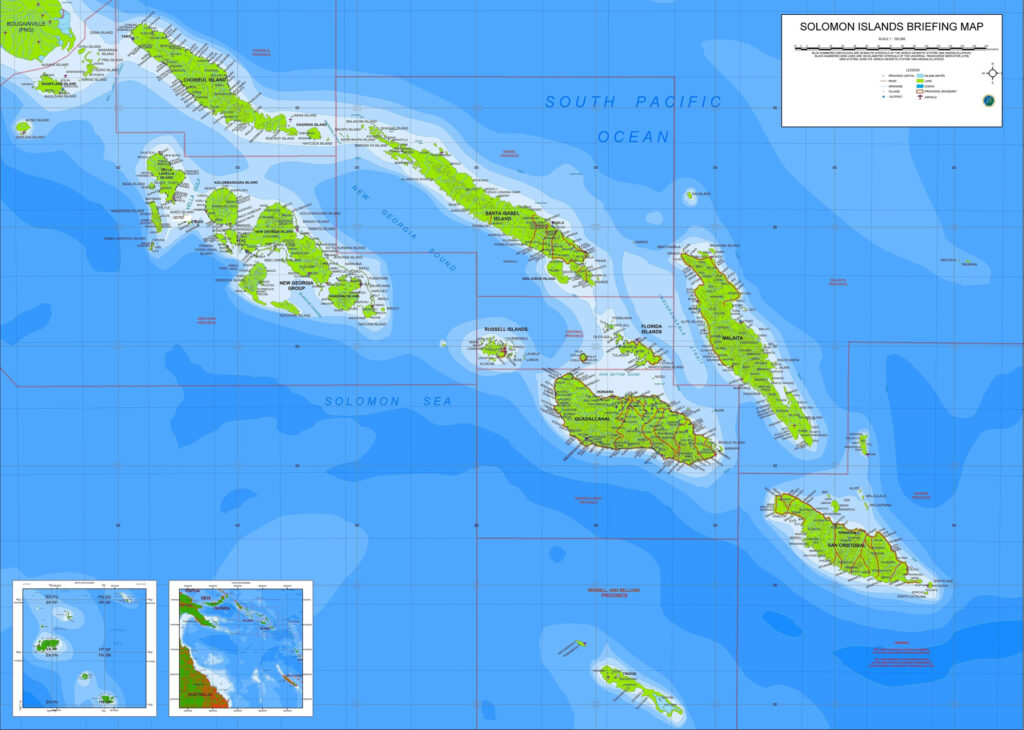

Increased ethnic rivalries created from disputes over land, movement and immigration in the Solomon Islands created political instability resulting in the necessity of foreign diplomatic intervention and a peace settlement in form of the Townsville Peace Agreement (TPA). The Solomon Islands are an archipelago in the South Pacific region consisting of more than 900 islands, with two Islands being populated predominantly – Malaita and Guadalcanal (Gyngell & Wesley 2007, p. 227). During the late 1990s, the political process in the Solomon Islands deteriorated and corruption created civil disturbance as the Guadalcanal people (the Guale) and Malaitans engaged in disputes over land. For the Guale, lack of infrastructure development to the north coast, perceived disregard for customs and increased dominance of Guadalcanal by the Malaitan immigrants caused ethnic resentment to the Malaitans (Moore 2018, pp. 165-167). This ethnic resentment escalated into conflict with the formation of armed militias in 1998, first with the formation of the Istabu Freedom Movement (IFM) that started dispossessing Malaitans of land and then the formation of the Malaita Eagle Force (MEF) by Malaitans with the backing of Malaitan sectors of the Royal Solomon Islands Police Field Force (RSIPF) in retaliation (Ibid, p. 166). The period that followed from 1998 is referred to as the Tension (1998-2003) as the Solomon Islands’ capital Honiara and surrounding areas were subject to clashes between the militias resulting in political instability and disorder (Ibid, p. 169).

A coup d’ etat in June of 2000 led by the MEF resulted in the forced resignation of Prime Minister Bartholomew Ulufa’alu creating increased political turmoil and a risk of destabilisation in the Solomon Islands. Concerned with preventing this disorder, John Howard’s government brokered a peace settlement through the Pacific Islands Forum in Townsville (Allen & Dinnen 2010, p. 306). This Townsville Peace Agreement (TPA) facilitated negotiations between the MEF and IFM leading to these militias disbanding with an International Peace Monitoring Team (IPMT) set up to monitor the situation as well as collect weapons for destruction (Hegarty 2001, p. 1; Barbara 2008, p. 129; Scales 2007, p. 207). Despite the initiative of the IPMT (2000-2002) to maintain a long-term peace in the Solomon Islands, ethnic tensions in the state were replaced by lawlessness and corruption from ex-Militiamen joining government law enforcement forces – renewing political disorder and instability (Hegarty 2000, pp. 1-2). The breakdown of law and order in subsequent years after TPA’s signing resulted in an incursion led by Australia in 2003, contributing significantly to the longevity of stabilisation in the Solomon Islands.

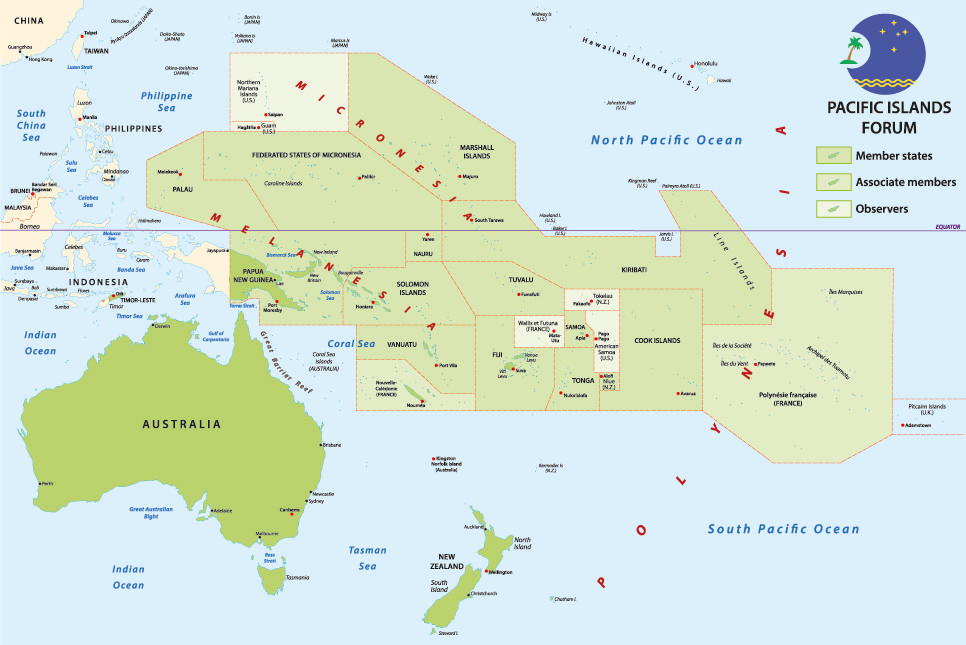

The Australian government’s involvement in the Solomon Islands reflects a risk management approach to the security of the South Pacific region and prevention of continued destabilisation from the arc of instability. The term arc of instability refers to security challenges facing Melanesia (the South Pacific) posed by the increase in terrorism, civil disturbances, transnational crime and political instability in the region during the 1990s onwards (Wallis 2015, p. 41). In the 1990s and early 2000s, the arc of instability was viewed with importance by Australian officials such as Prime Minister John Howard and Foreign Affairs Minister Andrew Downer. Both argued that Australia’s security in the South Pacific relied on the maintenance of stability in neighbouring states within the Melanesian arc. Through bilateral and multilateral involvement with these states in the form of financial aid, diplomatic and military support, it was argued that the potential risk of political and social disintegration as well as state failure could be countered – resulting in stability for states in the arc of instability and overall security for Australia (Wallis 2015, pp. 42-44; Dobell, pp. 89-93). This risk management approach to the security of the South Pacific was reflected in the Howard government’s involvement in peacekeeping missions in the South Pacific in the late 1990s and early 2000s, such as in East Timor in 1999.

The Australian-led United Nations peacekeeping mission into East Timor in 1999 reflected Australia’s perceived role as a responsible international actor for the security of the South Pacific and provided lessons to Australia of for future increased regional engagement such as with the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) in 2003. In 1999, the Australian government – under authorisation from United Nations Security Council (UNSC) Resolution 1264 – led a multilateral intervention through the multinational force of the International Force East Timor (INTERFET) to provide humanitarian assistance and re-establish order in East Timor (McDougall 2009, p. 188). This intervention into East Timor was prompted by ethnic tensions within the state, human rights abuses and a breakdown of law and order. Providing over five thousand Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel to assist in restabilisation of the state, Australia provided the bulk of troops for INTERFET (Cotton & Ravenhill 2012, p. 148). INTERFET’s objective started with police reform in within the state, before evolving into rebuilding the state’s governance structures and transitioning the state towards self-governance. This development was necessary for East Timor as it allowed for the state to return to stability with law enforcement returning to a competent capacity. The perceived success of the intervention by the Howard government set a precedent for future action within the South Pacific region (Ibid).

Australia’s approach under the Howard government was a departure to past approaches of respect for sovereignty in the region under Paul Keating’s Labor Party government (1991-1996). An increased regional engagement through interventions in the South Pacific, such as in East Timor normalised as the Australian government pursued a new role as a responsible international actor in the region (Cotton & Ravenhill 2012, pp. 148-149; McDougall 2017, pp. 461-463). This approach entailed active engagement in regional affairs in the South Pacific through diplomatic and military means. An early example of this shifting attitude was Australia’s handling of the Sandline Affair, where the then Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea Julius Chan attempted to resolve the ongoing conflict in Bougainville through the hiring of a private military contract force known as Sandline International. Australia’s interest in seeking a diplomatic solution to the conflict pushed the government to leak details of the secret deal to the press. Helping to prevent the deal from going forward successfully and preventing a military solution to the ongoing conflict. Australia learned a vital lesson from these endeavours in the south pacific: that intervention in pursuit of state-building in the South Pacific could be a viable means for regional stability and national security (Ibid). With this in consideration, the Howard government again pursued an intervention in the South Pacific through RAMSI in 2003.

The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) facilitated the reestablishment of law and order in the Solomon Islands through the assistance that the mission provided to local law enforcement, government and economy – highlighting Australia’s key role in the nation’s development. With political instability, corruption and lawlessness risking the collapse of the state, the Solomon Islands’ Prime Minister Allan Kemakeza asked for assistance from John Howard’s government in 2003. This request for assistance was accepted on the condition that a formal request from the Solomon Islands’ parliament be made (Gyngell & Wesley 2007, p. 228). Thus, giving the Australian government legal legitimacy to intervene without a breach being made in local national sovereignty or international law (Ibid). Through approval and negotiations with the Pacific Islands Forum, John Howard’s initiation of RAMSI facilitated the foundations for self-governance that was needed by the government of the Solomon Islands (Gyngell & Wesley 2009, p. 230; Cotton & Ravenhill 2012, p. 148).

Operation Helpem Fren [Helping friend] – another name for RAMSI – utilised the resources of multiple departments of the Australian government and other principle participating agencies such as the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), Australian Federal Police (AFP), Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), Defence and Treasury to engage in state [or peace] building (Ibid, p. 229). Over 1600 ADF personnel were deployed to Honiara along with 300 AFP to assist in the training of RSIPF, with the objective of eliminating the lawlessness, corruption and instability (McDougall 2009, p. 296-298; Cotton & Ravenhill 2012, p. 148; Barbara 2008, p. 132-133). RAMSI’s state building mission in the Solomon Islands was crucial for the development of the nation’s governance and infrastructure, with $840 million being invested by the Australian government between 2003-2006 into the project (Gyngell & Wesley 2007, p, 230). This investment allowed for the training of local law enforcement that helped to maintain law within Malaita and Guadalcanal by the dismantling of weapons and crackdown of criminal organisations [see Appendix, figure 1. 4]. Fundamentally allowing for the rebuilding of the machinery of government and democracy in the state (Moore 2018, pp. 172-174). Operation Helpem Fren completed its mission in 2017, playing a key role in the maintenance of peace, reestablishment of law and order and development in the Solomon Islands (Ibid, p. 175).

The Australian government’s involvement in the Tension period through the brokering of a peace settlement in 2000 and subsequent peacebuilding mission in 2003 during the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands was highly significant for the development of peace in the Solomon Islands. The Townsville Peace Agreement allowed for a peaceful resolution of ethnic tensions between the Guale and Malaitan militias – the Istabu Freedom Movement and Malaita Eagle Force. The disbanding of these militias along with the establishment of an Australian-led International Peace Monitoring Team to dismantle weapons and monitor the situation allowed for a temporary peace. The Melanesia arc of instability altered Australia’s approach to the South Pacific, with a more interventionist Australia arising through peacekeeping and state building projects in places like East Timor. Lessons learnt from East Timor allowed Australia to pursue increased regional engagement leading to intervention into Solomon Islands through RAMSI. RAMSI’s training and development of the Solomon Islands allowed for the reestablishment of law and order, elimination of corruption and rebuilding of the mechanisms of self-governance. This intervention into the Solomon Islands highlights Australia’s key role in the development of peace in the nation and stabilisation of the South pacific region.

Word Count: 1835

Written by Anthony Avice Du Buisson (20/05/2019)

+Reference List:

Allen, M & Dinnen, S 2010, ‘A North Down Under: antinomies of conflict and intervention in Solomon Islands’, Conflict, Security & Development, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 299-327, viewed 10 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2WbbVjD>.

Barbara, J 2008, ‘Antipodean Statebuilding: The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands and Australian Intervention in the South Pacific’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 123-149, viewed 11 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/30mUThX>.

Bohane, B 2000, A group of well armed guerrillas soldiers, members of the Isatabu Freedom Movement (IFM), stop…,awm.gov.au, viewed 10 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2WceIZK>.

Bohane, B 2000, Masked and armed Malaita Eagles Force (MEF) guerrillas gather on the outskirts of Honiara. This…,awm.gov.au, viewed 10 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2VFRUCm>.

Cotton, J & Ravenhill, J 2012, ‘Australia, the Pacific Islands and Timor-Leste’ in J Cotton & J Ravenhill (eds), Middle Power Dreaming: Australia in World Affairs 2006-2010, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, pp. 147-164.

Dobell, G 2007, ‘The ‘Arc of Instability’: The History of an Idea’, in R Huisken & M Thatcher (eds), History as Policy: Framing the debate on the future of Australia’s defence policy, ANU Press & Strategic and Defence Studies Centre (SDSC), Canberra, pp. 85-104, viewed 12 May 2019, <https://bit.ly/2HymdRz>.

Geocurrents.info 2014, Is There an Arc of Instability?, Geocurrents.info, viewed 13 May 2019, <https://bit.ly/30t1gAj>.

Gyngell, A & Wesley, M 2007, ‘Case Study: The Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands’, Making Australian Foreign Policy, 2nd edn, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, pp. 227-231.

Hegarty, D 2001, Small Arms in Post-Conflict Situation – Solomon Islands, State, Society and Governance in Melanesia Project, Pacific Islands Forum, viewed 11 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2Q5iyOW>.

McDougall, D 2009, ‘Southeast Asia: Indonesia’, in L Caiazzo, C Cooper, F Eden & J Whitton (eds), Australia Foreign Relations: Entering the 21st Century, Pearson Education Australia, Frenchs Forest, pp. 160-203.

McDougall, D 2017, ‘Peacekeeping from Oceania: Perspectives from Australia, New Zealand and Fiji’, The Round Table: The Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 453-466, viewed May 14 2019, <https://bit.ly/2Q6Fuxt>.

Moore, C 2018, ‘The End of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (2003-2017)’, The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 164-179, viewed 10 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2W8Npj5>.

Scales, I 2007, ‘The Coup Nobody Noticed: The Solomon Islands Western State Movement in 2000’, The Journal of Pacific History, vol. 42, no. 2, pp. 187-209, viewed 11 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/30rznIQ>.

Stephen, D 2003, Sergeant Adam Gilles of 2nd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (2RAR), holds a rifle from a…, awm.gov.au, viewed 18 May 2019, < https://bit.ly/2JKcKJw>.

Wallis, J 2015, ‘The South Pacific: ‘arc of instability’ or ‘arc of opportunity’?’, Global Change, Peace & Security, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 39-53, viewed 12 May 2019, <https://bit.ly/2VwfmwX>.

![The Rules-based international order [JCU Essay]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/united-nations-flags-700x422.jpg)

![Liberty and Responsibility: two sides of the same coin [Personal Writing]](https://philosophyismagic.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/1504224_699925763417223_1825504416239588555_o-700x465.jpg)